I originally started to write this post in reaction to a thread on the BIBFRAME email list in March 2015 entitled “Linked Data”. In reaction to this thread I wanted to write something on what I saw as the potential for Linked Data in libraries, which I felt went beyond the issues generally brought up in the thread (with a couple of notable exceptions). However, other things got in the way, and it wasn’t until I was invited to speak at an event on Linked Data and Libraries organised by OCLC that I managed to find the time to flesh out my thoughts. The following post is based on the talk I gave at that event which was on 22nd May 2015.

The accompanying slides are available and are licensed as CC-BY:

Anyone can say Anything

In the world of linked data it has been said that “anyone can say anything about anything“. This is both a huge challenge and opportunity for libraries wanting to exploit linked data. This talk will explore the ‘open world assumption’ of linked data, how it might benefit libraries and what approaches will allow libraries to take advantage of published linked data while trying to avoid problems caused by data of variable quality and veracity.

“With the Internet, we each have our own printing press”

Holbert, G.L. (2002). Technology, libraries and the Internet: a comparison of the impact of the printing press and World Wide Web . E-JASL, 3(1-2).

What’s the amazing thing about the web? What makes it different to what has gone before? One aspect is clearly the way in which information can reach many people in a very short time over long distances.

Another is the way in which it reduces the barriers to publishing information – and people have been extremely quick to take advantage of this. In 1991 there was one web site. 24 years later there are around one billion (http://www.internetlivestats.com/total-number-of-websites/). That’s a huge number and even with an estimate of 75% of these sites not currently in use, that’s still 250 million websites. Those 250 million sites are made up of a huge range of information of all kinds being published by all kinds of people and organisations: businesses, charities, museums, libraries and individuals.

This is possible because the web has a common system of addresses (URLs) and common standards on how to transfer information across the web (HTTP) and how to format the documents we publish (HTML).

“there may always exist additional sources of data, somewhere in the world, to complement the data one has at hand”

Learning Linked Data Project http://lld.ischool.uw.edu/wp/glossary/

What is the Open World Assumption? It basically says that others may know things that we don’t. That “there may always exist additional sources of data, somewhere in the world, to complement the data one has at hand” (http://lld.ischool.uw.edu/wp/glossary/).

This is as opposed to the closed world assumption, which assumes that you know and control all the relevant data. An example might be a seat booking system in a theatre or cinema – in such a system it is reasonable to assume that every seat on the system that doesn’t have a booking is currently free.

One of the things that typifies open world systems is support for making statements which negate information about things. If you operated a seat booking system with an open world assumption, for every seat that wasn’t booked you’d need to make an explicit statement to that effect.

A library catalogue as a whole generally operates on a closed world assumption – if there isn’t a record for a book in your catalogue, you don’t have that book. If a book isn’t out on loan, it is in the library (well, or lost or stolen!).

However individual records in a library catalogue – the bibliographic descriptions – tend to work on an open world assumption. For example, if the publisher of a book is not known, you can explicitly state that it is not known. This used to be done with [s.n.] (sine nomine), but now done with the slightly more prosaic “publisher not identified”. This allows us to differentiate between ‘not known’ and ‘not recorded in this catalogue record’.

But what has this go to do with linked data?

In 2006 Sir Tim Berners-Lee published a note on Linked Data (http://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html), this lays out the four things you need to do to have Linked Data. The first two of these are:

- Use URIs as names for things

- Use HTTP URIs so that people can look up those names.

That is essentially to say use web URLs as identifiers for things. This means that every one of those 1 billion websites I mentioned earlier is not only a place to host web pages, but also a place where identifiers can be created. If you have a website, you can publish your own linked data identifiers – it’s just more URLs.

The other two things in that note on Linked Data are:

- When someone looks up a URI, provide useful information, using the standards (RDF, SPARQL)

- Include links to other URIs. so that they can discover more things

Altogether these four things mean that linked data allows you:

- To create and publish unique identifiers for things you know about

- To make statements about things you know about using identifiers (your own, or other peoples)

- Enables you to say things about your own resources

- Enables you to say things about other resources

- Enables other people to say things about your resources

I described earlier how the web has made it possible to publish documents about things in a highly interoperable way using URLs, HTTP and HTML. In the same way Linked Data is a lingua franca for publishing data – it makes it possible for data from many sources, published by different people and organisations, to interoperate.

In particular I want to consider the point that publishing linked data, with your own identifiers, allows other people to make statements about your resources – linked data inherently works on the open world assumption. This is something I don’t think is considered enough in discussions of library linked data.

In March 2015 I attended the Early English Books Hackfest at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The event was to celebrate the release of over 25,000 texts from the Early English Books Online Text Creation Partnership (EEBO-TCP) project into the public domain. As is usual at such events, at the end of the day a number of people demonstrated or talked about the projects they had worked on during the day. There were a whole range of amazing projects, but one of the things that struck me was that several relied on the descriptive metadata, not the actual full text. Sadly, although the public domain texts do include some descriptive metadata, the underlying MARC records that describe the collection are not in the public domain.

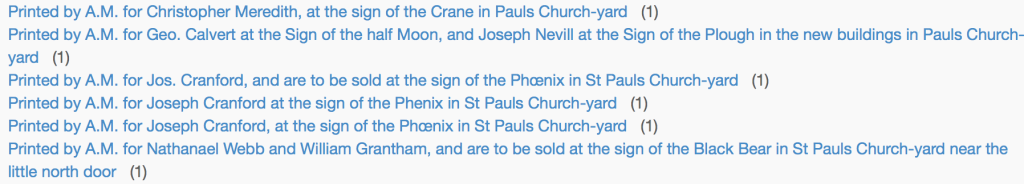

One project I was particularly interested in was looking at colophon statements. Colophons are typically statements of who published a book and when and where it was published. However the colophons for material in EEBO often contain more information than this, extending to information about where the item was to be sold. For example:

Printed by M. Flesher, for R. Dawlman and I. Rothwell, and are to be sold at the signe of the Brazen serpent, and Sun in Pauls Churchyard

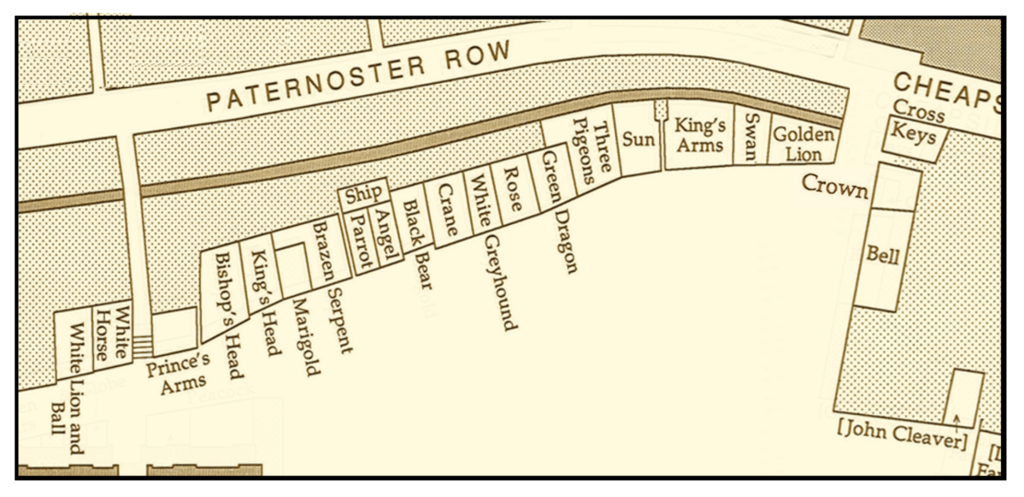

In the 16th and 17th Century Paul’s Cross churchyard (which is the site now occupied by St Paul’s Cathedral) was full of bookshops. These have been documented by Dr Peter Blayney in “The Bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard. Occasional Papers of the Bibliographical Society, 5. London: The Bibliographical Society, 1990.”

Just think what it would be like if Dr Blayney, or someone else, was able not only to do this research and record it, but publish it in a way that was intimately linked to the catalogue records that described the works being sold. Linked Data makes this possible. If the English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) which documents works published in the relevant period was published as linked data. Each work with it’s own linked data identifier. Then anyone, including Dr Blayney, could publish data which added to the knowledge that ESTC already represents, and link it to those records from the ESTC.

For the first time there is a way for experts anywhere in the world, no matter who they are to enhance library data in a way that can be captured and used – by them, by the libraries and by others.

Library data already operates on an open world assumption. It is time for us to embrace the full meaning of this – that we are not the experts on the resources we hold, and that potentially there always data in existence elsewhere that complements ours.

What sort of opportunities would be offered by enabling and embracing others to make statements about library data? Three things immediately come to mind:

- Improved displays in our discovery interfaces

- Improving our data by finding incorporating corrections to our data

- Improved search and discovery through the use of external data in our indexes

I created a demonstration of how linked data could be used to enhance displays in library catalogues with the “Composed” bookmarklet which I’ve blogged previously at http://www.meanboyfriend.com/overdue_ideas/2011/07/compose-yourself/

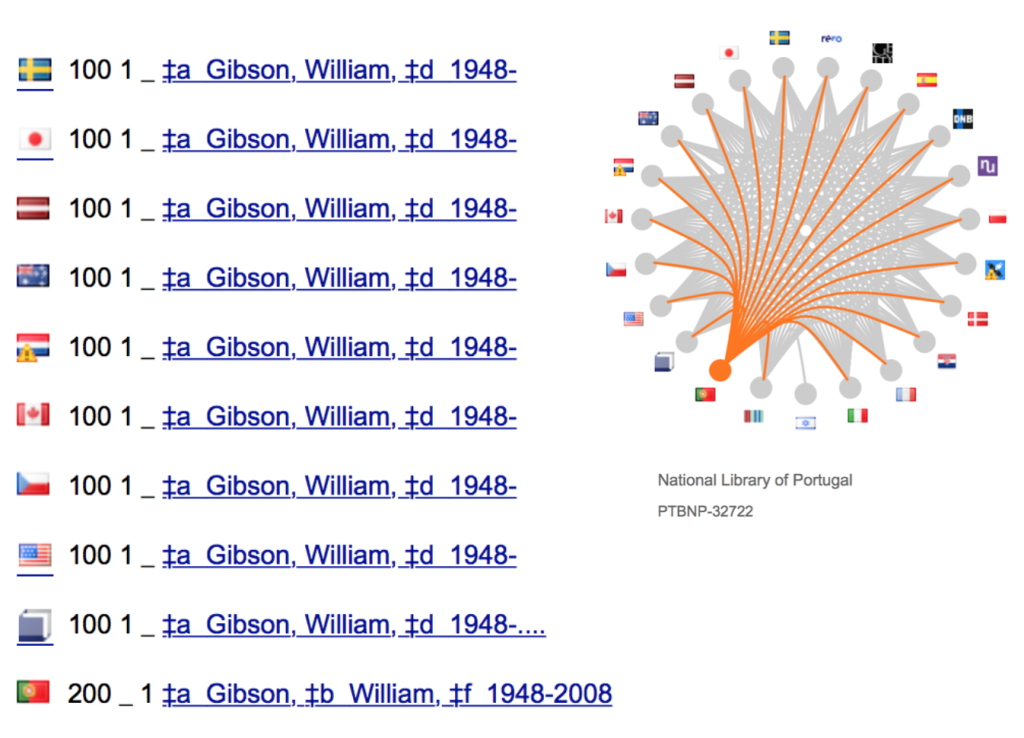

In terms of data corrections we can see the potential of this if we look at the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF) record for the science fiction author William Gibson on VIAF:

VIAF has become a key Linked Data resource due to the number of people and organisations it identifies. However, in this example I want to highlight how that data can bring to light inconsistencies in our data, and it should trigger the question ‘have we got this right?’

How do people tell you you’ve got things wrong in your catalogue at the moment? What if they could publish corrections (or at least their view of things) in a way we could use gradually to improve our own data?

Here we can see that unlike all other libraries in VIAF, the National Library of Portugal thinks that William Gibson died in 2008. Whoever is correct, this anomaly at least should trigger the question “which of these statements is correct?”

If we published library data as Linked data and encouraged others to publish linked data statements about our stuff it would open up the ability to see where our data was wrong, or at least where there was disagreement.

Finally in terms of using linked data to improve search and discovery in libraries I want to go back to the example of the bookshops in Pauls Cross Yard. If Peter Blayney had been able to link his knowledge about the booksellers and their shops to library catalogue records or even to the level of colophons in library catalogue records – it would then be possible to bring this data into library discovery services. Imagine how the ‘publisher browse’ shown below could be improved by using the information from Peter Blayney’s research:

This could change the nature of the catalogue:

“The catalogue could be an information source, rather than just an inventory”

Karen Coyle in “Catalogers + Formats, the Wider Web – Open Discussion” https://youtu.be/OtY3bWhUT9M?t=2371 (39mins 30 sec)

The opportunities offered here are large, but there are problems as well. “Anyone can say Anything”. We know the web is full of mis-information (deliberate or otherwise) and not only that, there can be legitimate disagreement on a topic.

So is this just a free for all? Yes and no.

In general terms it is a free for all – anyone can say anything. But in terms of the data we choose to use – that’s up to us. We need to care about the provenance of the data we use. We can select those sources we trust, and ignore those that we don’t. We can look for contradictions in data we can see and use that to flag issues.

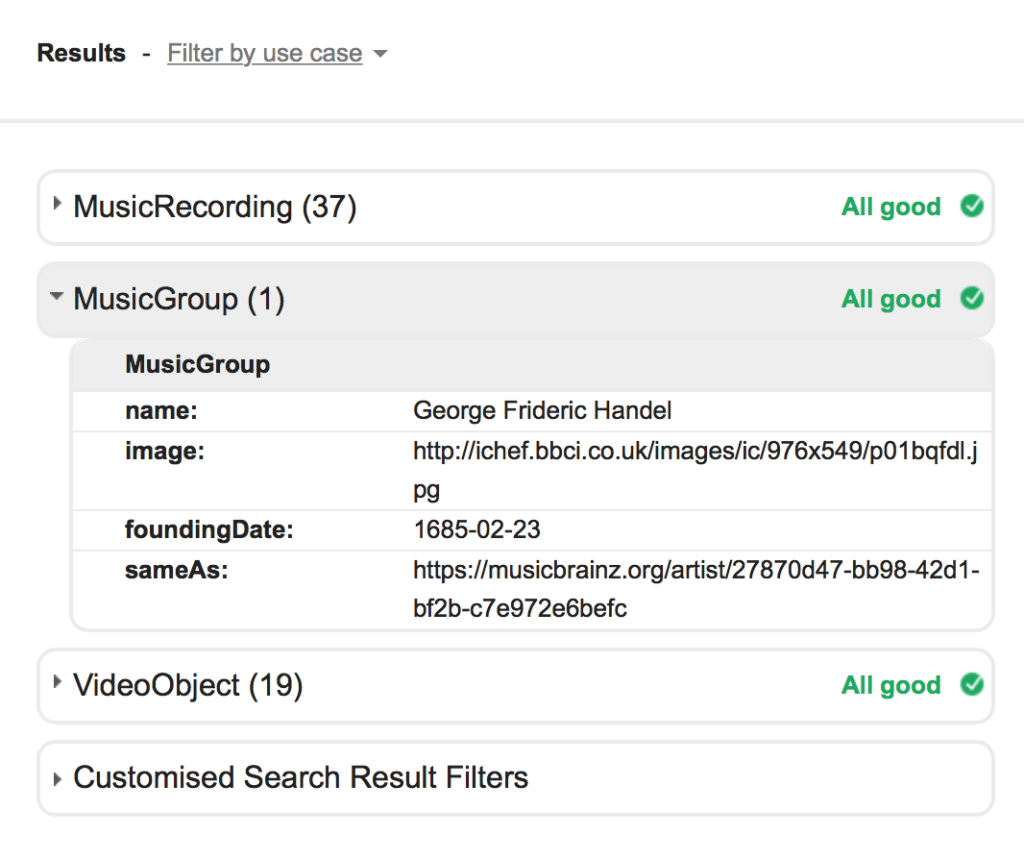

For example – maybe we would trust information about musicians from the BBC

This screenshot shows linked data (using schema.org) extracted from the BBC page about George Frederick Handel. It includes an image of Handel and his exact date of birth, as well as a link out to more information in MusicBrainz. It also contains a list of recordings and video material relating to Handel.

It’s a rich resource, and just one of many we could make use of in libraries.

But as well as looking to these trusted organisations, we should look to the expert individuals. These are people in our institutions and communities, and who have spent years developing expertise in their chosen fields – Linked Data gives us a chance to work with experts across the globe, and harness that expertise to improve what we do

We live in an open world – we can’t assume that what libraries, or indeed other cultural heritage institutions have chosen to record, is the end of the story. Peter Blayney has been researching and documenting information on the book trade in 16th and 17th Century London for 20 years – I think we can trust the information he publishes as much as any we create.

So libraries should:

- Coin identifiers for things we know about

- Work with others to get them using those identifiers – this latter point, in my opinion being a vital part of what we need to do

If we publish RDF, but don’t embrace the open world assumption that goes with linked data, we have not much more than just another way of formatting our data. We need to go beyond this and understand what it really means to be Open.