“Openly Connect” was the title of a talk I gave at Internet Library International 2011 (tipping my hat slightly to Only Connect, the BBC4 quiz show). I’ve been wondering about the best way of sharing the presentation online, and decided that really blogging the ideas is much more useful than just dumping the slides somewhere.

I believe that libraries, museums and archives are not getting the most out of the data about their collections, because they aren’t publishing in ways that enable or encourage others to take the data and use it in new, innovative (or even boring), ways. I think we need to offer data more ‘openly’.

Being open

(Image courtesy of withassociates, CC-BY-SA)

But what does ‘open’ mean in this context? For me, this is not a simple binary open/closed… but rather a continuum. There are a range of factors that affect whether others can easily take, and reuse, your data. But it is easy to focus on a single factor when talking about ‘openess’ – especially to focus on ‘rights’ to reuse data – copyright, database rights, licensing, terms and conditions etc. While these are an important factor, they are not the only factor.

Paul Walk puts it better than me in this slidedeck when he argues we need a ‘richer understanding of openness’ which encompasses not just permissive licensing but, more broadly, the ease with which data can be used, taking into consideration aspects such as format and access mechanisms

Friction

I’ve started to think about factors affecting reuse as being causes of friction (an idea I’m pretty sure I got from Tony Hirst). This may not be an exhaustive list, but the things I can see that create friction in the reuse of data are:

- Explicit restrictions on reuse

- Uncertainty about possible restrictions on reuse

- Unusual or unfamiliar interfaces and formats (if you don’t work in the library world, you’ve probably never heard of Z39.50, and yet this is a standard machine to machine interface supported by many library systems)

- Lack of information on data and where the data is available

Sometimes you might deliberately introduce friction – perhaps you don’t want your data to be reused by just anyone, for any purpose. I don’t see friction as bad per se – we just need to be aware of it, and especially avoid introducing friction when we don’t mean to.

Oiling the wheels

There are clear steps that a library, archive or museum can take to ensure there is no unwanted ‘friction’ in the reuse of their data.

1. Apply clear licensing or terms on reuse.

As a signatory of the Discovery Open Metadata Principles, I believe descriptive metadata, such as that in library catalogue records, should be licensed as ‘public domain’ data (using CC0 or ODC-PDDL or equivalent).

However, if reuse is restricted for some reason, be clear about what those restrictions are. Commercial services like Twitter offer clear terms of use on their APIs – these are restrictive, but clear. Similary Wired magazine’s recent decision to offer images under Creative Commons BY-NC, while falling short of ‘open’ offers some level of clarity. In the latter case, the use of the ‘NC’ (Non-commercial) clause can lead to uncertainty about rights for reuse – as noted in this article.

The JISC Guide to Open Bibliographic Data might help inform decisions about licensing metadata, as may the Discovery licensing guide.

2. Adopt widely used (machine) interfaces and formats for data

While any access to machine readable data increases the opportunities for reuse, adopting widely used interfaces and formats – ones for which a wide range of code libraries and tools will be available, and which the development community will be familiar with. Currently this often boils down to offering an interface that delivers data in XML or JSON format over an http interface. Sometimes the term ‘RESTful API’ is used to describe this kind of interface, although it should be noted that in reality providing a RESTful interface is a bit more than just xml/json over http. This article tries to explain more specifically what REST is.

3. Document your APIs and your data

Whatever interfaces/APIs and data formats you support, leaving them undocumented immediately increases friction on reuse. Many of the systems libraries, museums and archives use provide some API, but these are very rarely clearly documented by the organisations using the systems. Without documentation, it’s a huge amount of work for a developer to work out how to interface with the system.

For example, my local public library uses the Aquabrowser interface to their catalogue, which supports a couple of APIs – but in order to use these I had to find out the details of the API from the University of Cambridge documentation, and then apply the details to the public library system. Even just pointing to documentation held elsewhere helps – and sends the message ‘we want you to use this API’ – and without this, the API will be left unused.

The data we deal with in libraries, museums and archives is specialist, and often confusing to those not familiar with the details – therefore not just documenting the APIs available, but also the data available via those APIs (this is also a reason to offer simple representations of data, as well as fuller, more complex, expressions as appropriate).

Finally, data needs to be ‘findable’ – how would a prospective user of your data know what data you have, and where to find an API for it? In Australia the Museum Metadata Exchange is an interesting model for making this information available, but there are also more general tools/sites like like http://thedatahub.org/ and http://getthedata.org/.

4. Use common identifiers

This probably seems less fundamental than the points above, for me it is absolutely key. The point here is that if anyone wants to combine data together, common identifiers across data sets are what they will be looking for – and I’d argue this is going to be a pretty common use case for your data, or anyone elses, by a third party developer.

While it is possible to write code that tries to match strings like “Austen, Jane” in your data to http://viaf.org/viaf/102333412/, this is much more effort and much less precise than if a shared identifier was used from the start. It’s no surprise that if you look at many mashups created using bibliographic data they rely on the ISBN to match across different data sources (for example, pulling in cover images from Amazon, LibraryThing, Google Books or Open Library).

Supporting Discovery

Much of my thinking in this area has been informed by my work with the ‘Resource Discovery Taskforce‘ and with the Discovery initiativethat followed the work of the taskforce. Discovery is an initiative to improve resource discovery by establishing a clear set of principles and practices for the publication and aggregation of open, reusable, metadata. So far Discovery has published a set of Open Metadata Principles, and a set of draft Technical Principles, as well as running several events and a developer competition.

There will be a lot more coming out of the Discovery initiative over the next few months, and you can follow these via the Discovery Blog (which I occaisionally write for).

Outcomes of Open

Examples

Rufus Pollock, the Director of the Open Knowledge Foundation, said “The coolest thing to do with your data will be thought of by someone else” – but is this true? Perhaps obviously, it isn’t a given that anything will happen when you publish your data for reuse. However, there are now plenty of examples of interesting applications being built on data that has been published with reuse in mind. To just pick a few examples:

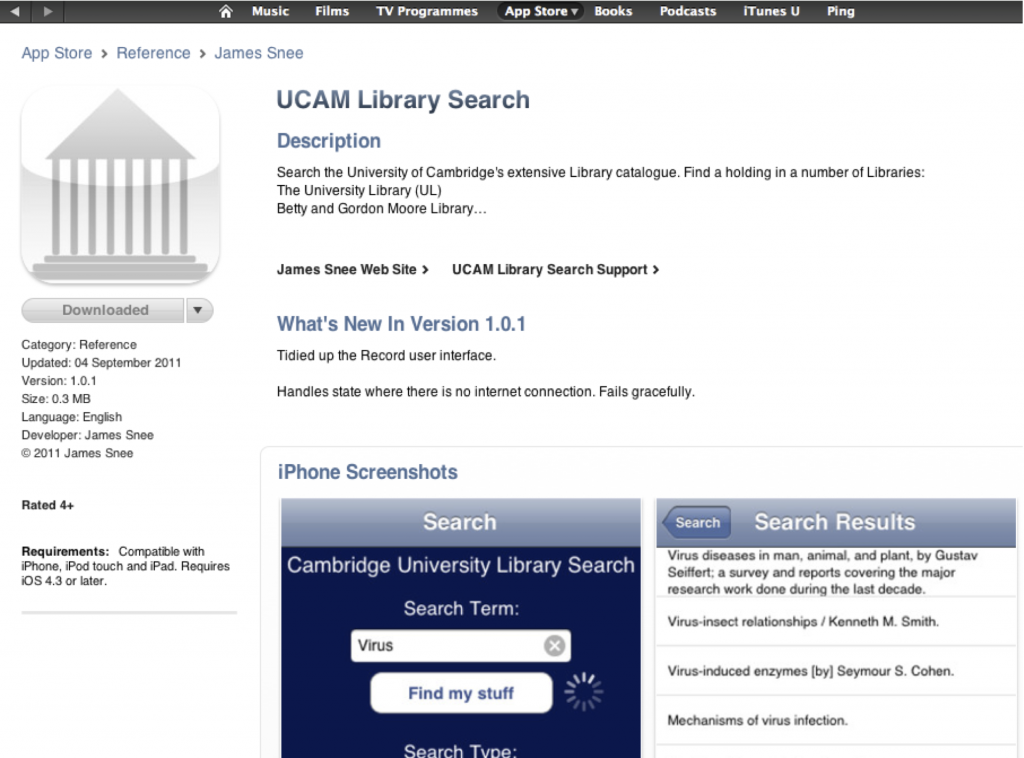

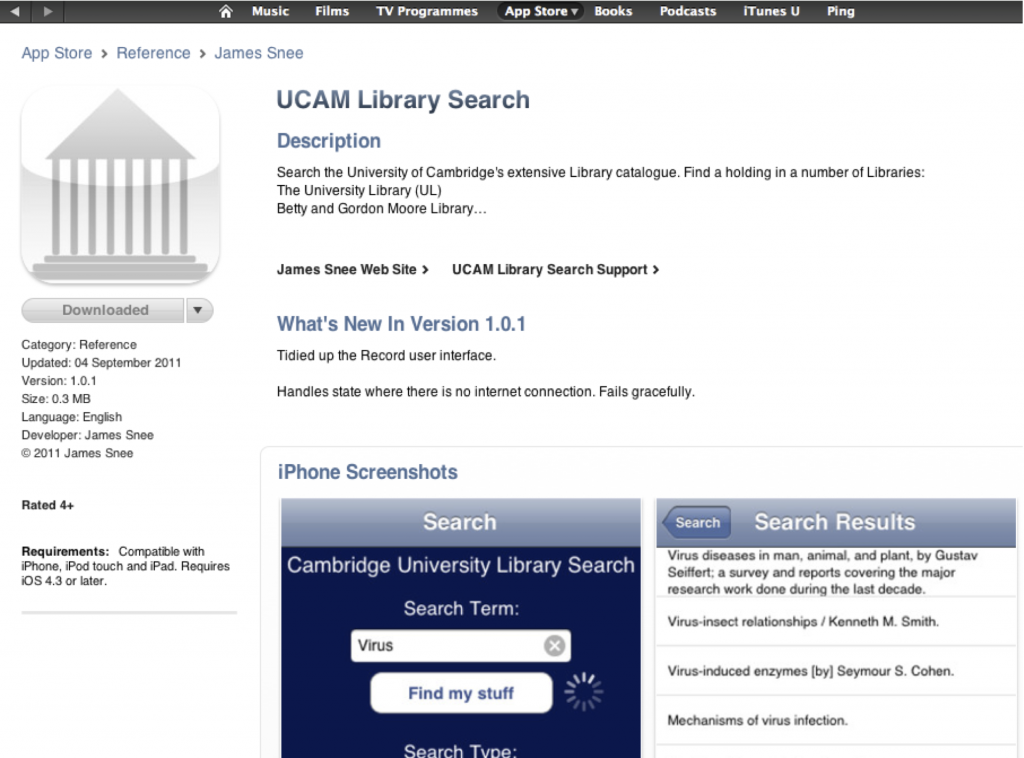

This iPhone app to search Cambridge University Library was developed by a postgraduate student – just because they wanted to learn how to develop an app using JSON, and found the API documentation published by the library.

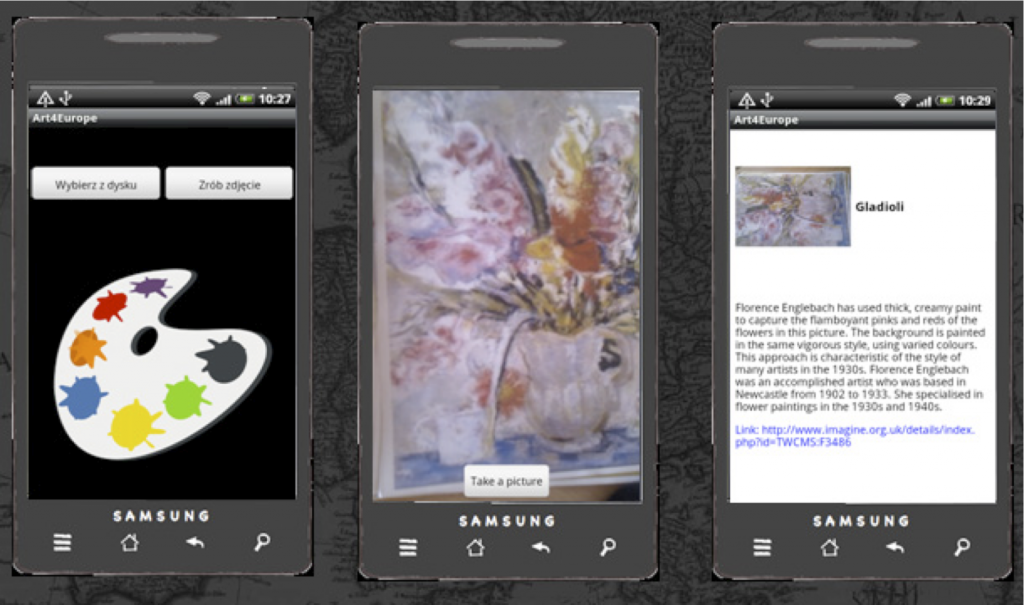

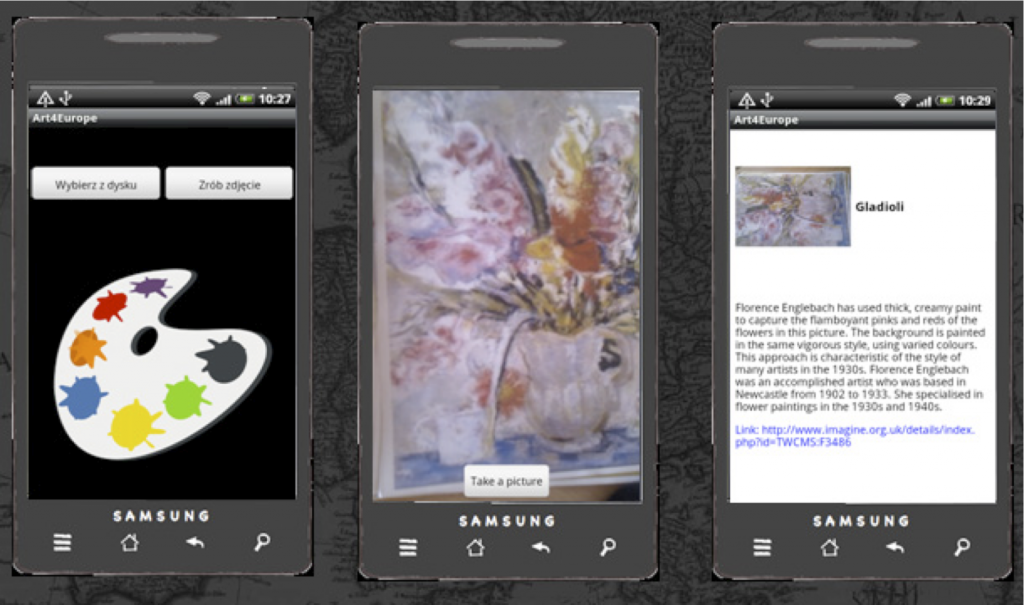

This app allows the user to take a picture of a work of art using their smartphone, and then retrieves information about the item from Europeana – it was built as part of a ‘hackday’ for Europeana.

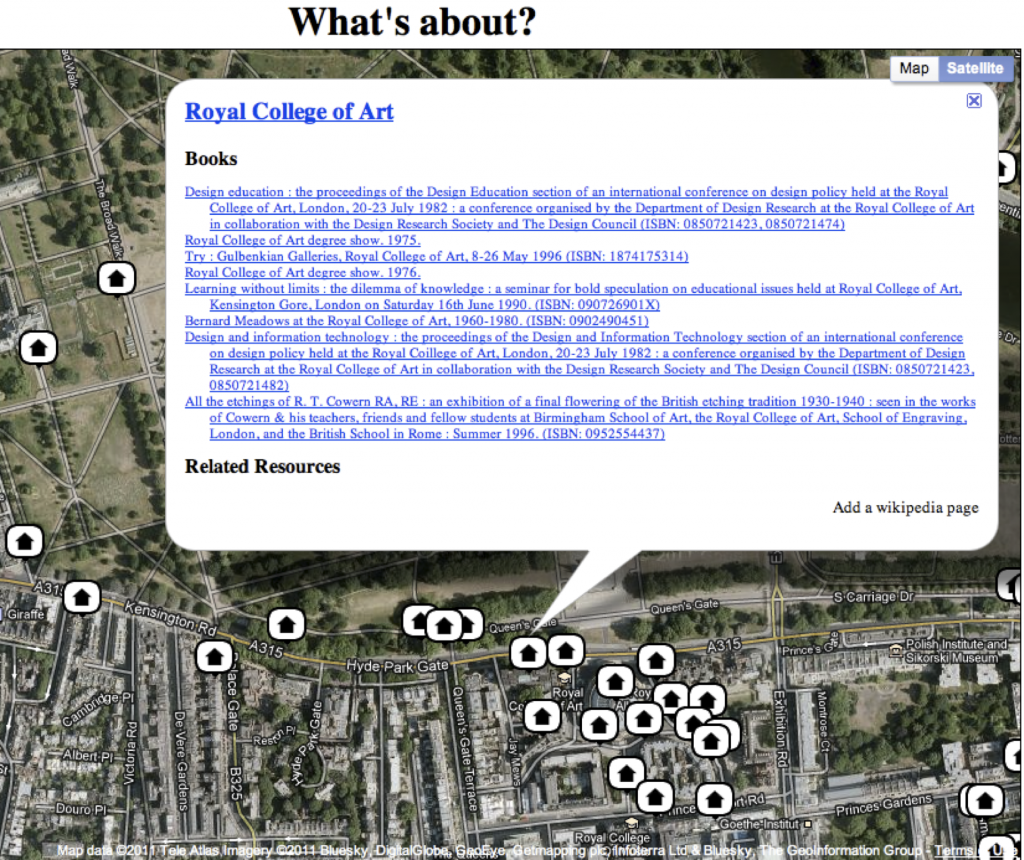

This novel interface to pictures from the National Archive was built as part of the Discovery Developer competition.

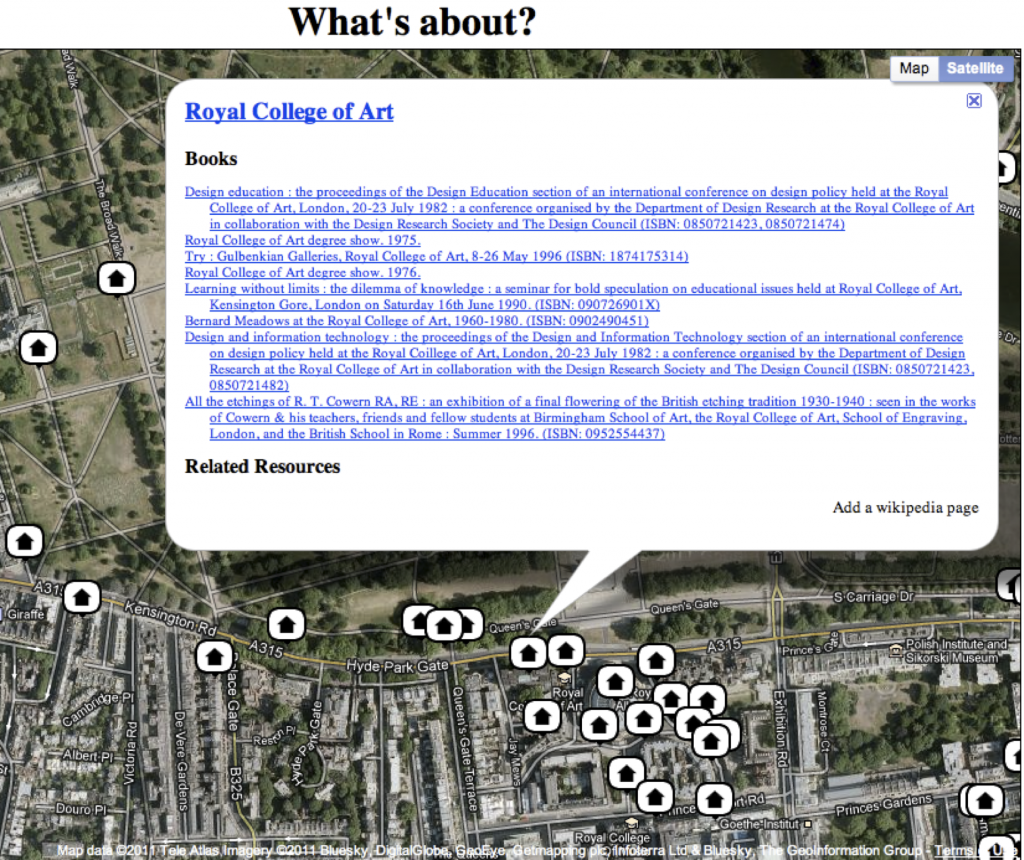

This map brings together information from English Heritage and the British National Bibliography to display location specific information.

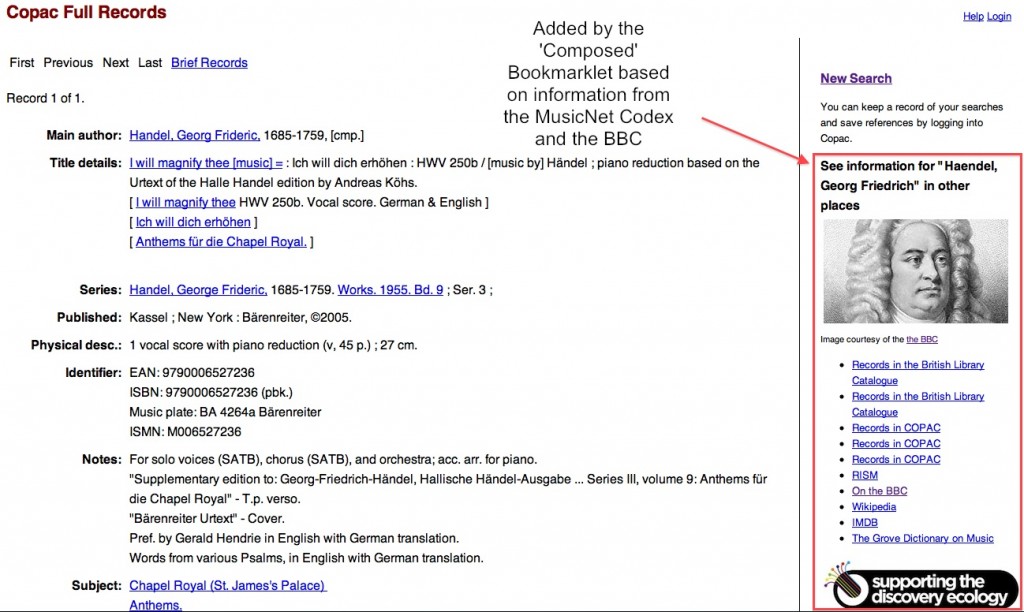

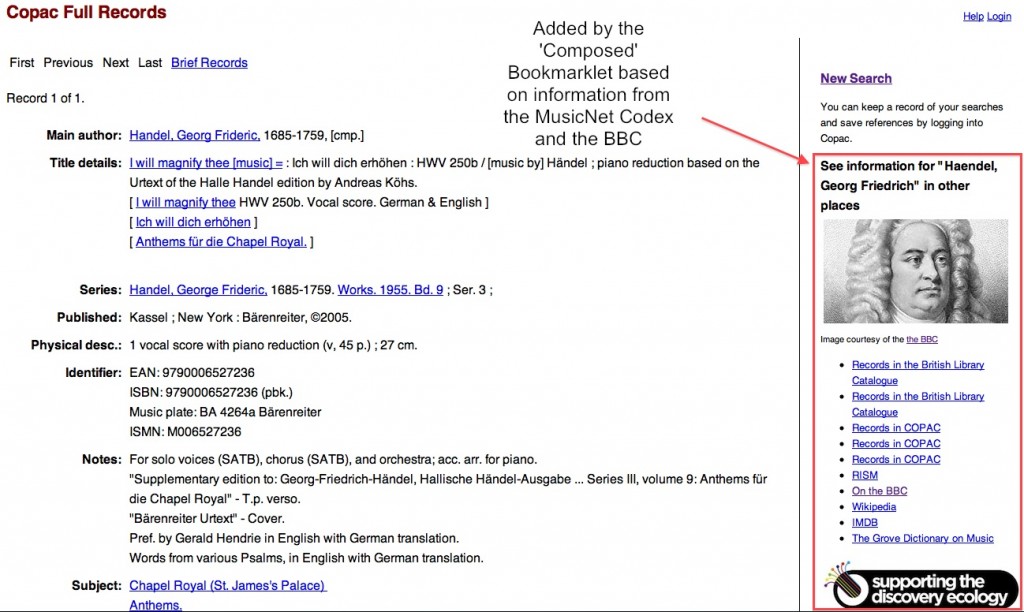

… and finally to blow my own trumpet, this bookmarklet I’ve already written about

Supporting developments

Something I don’t feel I really understand yet is how data suppliers can best engage with developers who might build on their data. Emma Mulqueeny (@hubmum) has written eloquently about engaging developers, but I’m still not sure I fully understand the best way that an organisation such as a museum, library or archive can engage with the development community.

Except the Cambridge University Library iPhone app, all the examples above are the results of some explicit stimulus – a competition or hackday. I don’t think any of them can be described as ‘production level’ – they are, in general, proof of concept. If publishing data is going to result in sustainable developments, we need to consider how this is supported – should organisations ‘adopt’ applications or developers? Should they work with relevant organisations to realise some commercial benefit to the developers? Are there other approaches?

I’d say at the least provide somewhere for developers, and potential developers, to talk to you, ask you questions, get permission to try stuff out – that dialogue is at least the first step to something more sustainable.

Take action

After my presentation at ILI 2011, which covered much of the same ground as this blog post, I felt that perhaps I’d missed a key point, and an opportunity while I had an audience – the question of what they should do in light of what I was saying. So, not wanting to make the same mistake again, I would encourage, even exhort, you to take the following actions:

- Explicitly license your data – whatever it is, put a license on it, be clear about what people can or can’t do with the data, and publish those details on your website

- Find out about, and document, any APIs you already have to your data – it might be z39.50, it might be SRU/SRW, it might be some RSS feeds – whatever it is, write a short page that says where the API/data can be accessed, some basic instructions on how to use it. Be clear what you expect from people interacting with your data (both in terms of licensing – point 1 – and anything else like “please don’t kill our servers”)

- Create a place for developers to communicate with you (or hang out somewhere that you can communicate them)

If you can’t do any of these things yourself, find out who can answer the questions, or make this happen – find out if they are interested, and if not, why not and what the barriers are (and then let me know!)