Yesterday was Mashed Libraries UK 2008 – the first in what I hope might be a series of Library Mashup/Tech events in the UK.

The idea of holding the event germinated while I was at ALA earlier this year, inspired also by the Mashed Museums event. I blogged the idea, and before I knew it, had offers of rooms, sponsorship and quite a few people saying they'd like to come along.

Some questions, and answers about the event:

Did it go well? I hope so. It was a bit like hosting a party – you spend the whole time worrying if people are enjoying themselves, and then when its all over, you’re knackered!

What did we do? I’d worried quite a bit about the structure of the day. I knew I had a real mix of people coming along and I wanted to ensure that everyone felt there was something for them. I’m not sure I completely succeeded, but I think the mix was OK.

The day started with some presentations from Rob Styles (on the Talis Platform) and Tony Hirst (on mashup tools like Google Spreadsheets and Yahoo Pipes). A third speaker was planned, but unfortunately unable to make it, so a few people agreed to help fill (Timm from Ex Libris, Mark from OCLC and Ashley from MIMAS – thank you)

What surprised me (but perhaps was not really surprising) was the extent to which these presentations set the agenda for the day – people tended to look at the stuff covered in these presentations. This isn’t a bad thing at all, but worth noting when planning this kind of event.

After the presentations (done by about midday) we broke for lunch, and people chatted etc. After this, I really left it up to people as to what they wanted to get on with. I’d collected some ideas on the Mashed Library Ning beforehand – but on the day the content of the presentations influenced what people did much more than this.

I wasn’t sure how to ‘manage’ the more free-form part of the day – how to make sure that people weren’t left thinking ‘what on earth do I do now’, while still ensuring that people could get on with what they wanted. I think it worked – but perhaps others are better placed to say.

Some of the things that people did on the day were:

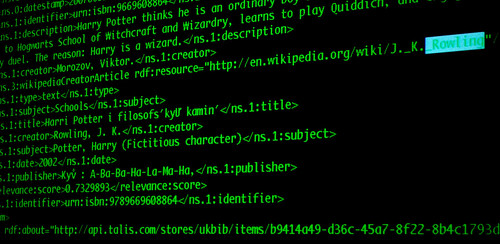

Mash along with Tony Hirst – Tony conducted a Gordon Ramsay style mash along using Yahoo Pipes to pull data from different bits of the Talis Platform, and trying to output locations of books plotted on a map. There were some problems, and the limitations of Pipes become apparent (as well as issues with aspects of the data)

Rob Styles and Chris Keene (Sussex) were aiming at something similar, but with PHP and Javascript, and additionally pulling in data from another Talis source ‘Silkworm‘ – a directory of library information (including more detailed location information)

Matthew Phillips (Dundee) and Ed Chamberlain (Cambridge) played around with output from the Aleph API and Pipes (unfortunately some real challenges with this one), and Matthew also showed off his use of graphical bars to illustrate overlapping journal holdings – in print and from various supplier electronically.

A few groups messed with Pipes and locations – finding the nearest Travel Agents, Museums and Pubs to a specific location.

David Pattern (Huddersfield) messed around with usage data, trying to see if heavy use of one book today meant that another title would be in high demand next week, to allow planning of moves of titles into Short Loan etc.

Nick Day (Cambridge) used WorldCat to look up identifiers for citations he had coded up in RDF from some PhD Theses.

There was also the chance simply to soak up the atmosphere, wander round to see what others were doing, and generally chat and network.

Towards the end of the day Paul Bevan from the National Library of Wales talked about how they were engaging with Web 2.0, and the different challenges that they faced compared to ‘academic libraries’. (and sadly we were lacking attendees from the public or commercial library sectors)

A collection of pictures from the event is forming on Flickr, and I took some video footage on the day, which I hope to turn into something – I’ll post it here when it’s done.

What would you do differently? I’d remember that a room full of people with laptops needs lots of power points. The room we had unfortunately only had 6 – but with a bit of help from the local support staff, and a local Maplins, this was sorted out before people ran out of juice

I’d also remember that you need to order Vegan options for Vegans (I’m really sorry Ashley – hope you did get something to eat)

Thanks to? Thanks to Imperial College for letting me spend time organising this; UKOLN for sponsoring it (without whom, there would not have been cake); Paul Walk (of UKOLN) for encouragement and arranging the sponsorship; David Flanders (Birkbeck) for sorting the room, local details, and generally being helpful; all the presenters; and everyone who came along and contributed to the day.

In Summary? I didn’t really have any huge expectations of the day – I wanted it to bring together a group of interested people, and do some interesting things. I hope that the people who came along felt that in the main we managed this.

I can definitely see potential for different kinds of events that perhaps focus on more development, or on training – if you weren’t able to make it, then you might consider going to the JISC Developer Happiness days in February next year, which include an introductory day to develop skills, as well as a 2 day coding session (with prizes).

I think overall I can say Mashed Library ’08 was a success. I’d like to do another library tech event in the new year – so if you are interested, keep watching, or drop me a line.

Photos courtesy of Dave Pattern, via Flickr